She has one of the most important jobs in the world, but most people outside of the Idaho factory where she works have never even heard of what she does.

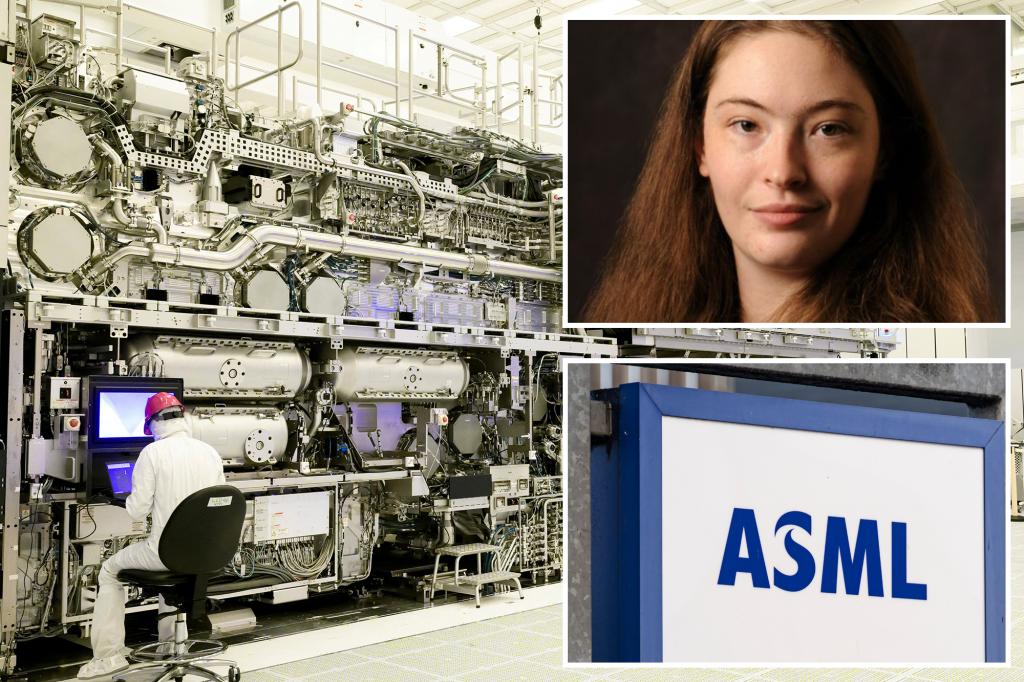

Brienna Hall, 29, is one of a relative handful of elite engineers trained to maintain and operate extreme ultraviolet lithography machines —highly complex devices known as EUVs that create the microchips iPhones, computers, televisions, cars and more depend on.

“I thought I had the coolest job ever,” Hall told the Wall Street Journal.

“I didn’t process the fact that this job is necessary for our entire world to exist as it does,” she added.

Hall, who refers to herself as a “fancy mechanic,” is customer-support engineer for ASML, the Dutch company that invented EUVs and is the only one making them toda. The business depends on her and about 10,000 similarly trained colleagues to maintain every one of the few hundred EUV’s manufacturing the world’s microchips.

The machines — which are roughly the size of a bus — border on science fiction, and create microchips by vaporizing drops of molten tin, then blasting the metal with ultraviolet lasers to leave an imprint of a chip-pattern on silicon wafers.

That process occurs 50,000 times a second, and creates chips with details 10,000 times finer than the width of a human hair.

They also use mirrors so perfectly rendered that if they were blown up to the size of Germany, the biggest imperfections would be smaller than a millimeter, according to the Journal. And their lasers are precise enough to shoot a ping pong ball on the moon’s surface.

Of the few hundred EUVs in existence, only six companies own their own. The rest of the world depends on ASML to create the chips for them.

That’s where Hall — who works at ASML’s Boise plant — comes in.

A Washington State University graduate who majored in engineering and materials science, Hall got the job after a professor passed her resume to ASML and the company reached out requesting she apply.

Hall had never heard of ASML or an EUV, but was sold when they told her the extensive training would take her across the world.

She first travelled to Taiwan where she spent a month learning about an EUV’s 100,000 parts, then shipped off to Germany and San Francisco for months at a time before her entry-level training was done.

Then it was another year of apprenticeship before she was allowed to work on an EUV alone.

When she walks into the EUV’s room — where the air is 100 times cleaner than a hospital operating room — the first thing Hall does is don a decontaminated full-body suit so as not to alter the precise conditions needed for the machine to operate accurately.

“Everything must be perfect,” Hall told the Journal. “The conditions must be just so for her to function.”

The devices can be affected by the likes of earthquakes — and a malfunction in one was once even traced to methane flatulated from cows at an upwind dairy farm.

Hall is the kind of person whose job it is to dissect the machine’s problems and figure out such causes, and monitor the machines daily to make sure others don’t arise.

She works in 12 hours shifts, and tries to use the bathroom as little as possible to keep from contaminating the machine-room with comings and goings.

“I’ll space out and limit my sips of water — and I won’t drink coffee,” she said.

She revels in the intensity of the job.

“When I’m on the tool and fixing a problem, it’s like everything else goes quiet — and I’m just focused on getting that one thing done,” Hall said.

“There’s nothing better than just zeroing in on that problem until it’s solved.”

But despite the EUV’s enormous complexity, Hall thinks they’re easier to work on than any given human.

“Our machine is complex enough that it has a personality, but it’s still a machine. If you hit the right buttons, she will come up. You just have to figure out what buttons to press. I can solve that. We can solve that,” she said.

“Humans are vastly more complex than any machine that I know of.”

Read the full article here