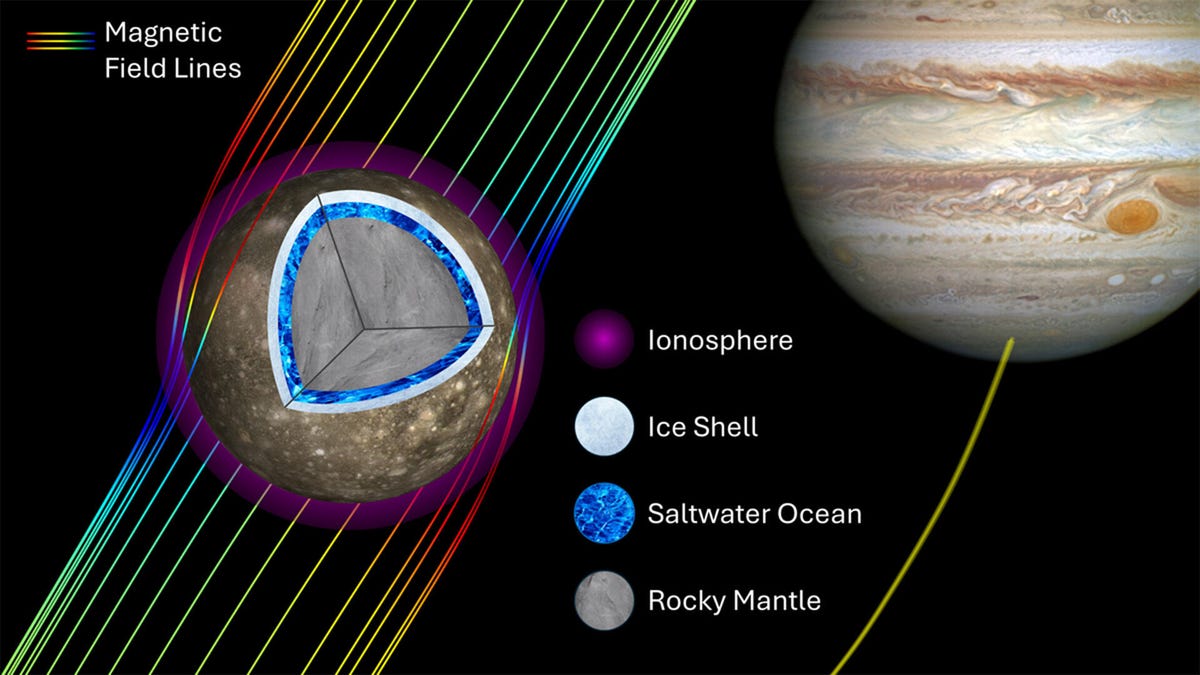

If there was a contest for the most interesting moon in our solar system, Callisto would be a contender. Jupiter’s second-largest moon has more impact craters on its surface than any other planetary body in the solar system, and it has tons of ice on its surface as well.

For decades. researchers have theorized that resting beneath Callisto’s pockmarked surface is a liquid saltwater ocean that spans the entire moon. After taking a closer look at data from 30 years ago, researchers now have stronger evidence that such an ocean really does exist.

A team led by Corey J. Cochrane of NASA’s Planetary Interiors and Geophysics Department didn’t start out looking for an ocean on Callisto. According to Cochrane, the team was working on a different project, involving scanning Neptune’s moon Triton to see if it has a subsurface ocean.

This presented a challenge, because of Triton’s intense ionosphere, which is the last layer of the atmosphere before space begins. Since Callisto also has an intense ionosphere, the team decided to test their methods on 30-year-old measurements taken by NASA’s Galileo mission. That mission launched in 1989 and scanned Jupiter and its moons between 1995 and 2003.

“Our conclusions were enabled by analyzing measurements that were acquired from a flyby of Callisto that has typically been neglected in the community due to the presence of increased ‘noise’ attributed to the plasma environment,” Cochrane told CNET in an email.

“We were able to leverage previously developed plasma simulations to remove this obscuring plasma noise source from the measurement so that the signal from the ocean could be analyzed independently,” Cochrane said.

In short, Galileo’s readings were initially difficult to interpret because of Callisto’s strong ionosphere. Once Cochrane and his team cleaned up the readings, they were able to consider the data, and it strongly suggests there’s an ocean under the moon’s rocky exterior.

The ionosphere looks like an ocean

It’s taking so long to prove the existence of a subsurface ocean on Callisto because a strong ionosphere mimics the readings you’d get if there were such an ocean.

“A fundamental physical law of nature (Faraday’s Law of Magnetic Induction) indicates that if you move a magnet with respect to any conductive material, like a copper wire, you will create an electrical current within that wire that is synchronized to the movement of the magnet,” Cochrane explained. “That current will then create a secondary magnetic field (due to the movement of the electrons in the wire) which is called an induced magnetic field, which exhibits properties of the conductive material.”

Cochrane said this works with planetary bodies as well. Moons or planets with enough internal heat can have a liquid saltwater ocean beneath the surface. These oceans are electrically conductive thanks to the salt in the water. Thus, scientists can use magnetometers to measure an induced magnetic field that “retains properties of the ocean,” Cochrane said. In other words, oceans can be found based on the magnetic fields they generate.

Since moons like Jupiter’s Callisto and Neptune’s Triton have very strong ionospheres, readings with a magnetometer become so noisy that researchers have trouble figuring out whether what they’re looking at is an ocean or just random noise from the extra energy in the ionosphere. That’s why researchers have been stuck on Callisto’s potential underground ocean for decades.

The next steps

Science won’t have to wait another 30 years to find proof. NASA’s Europa Clipper mission set sail last year and should reach Jupiter and its moons in 2030, while the European Space Agency’s JUICE mission should arrive in 2031. Both missions will almost certainly provide more research data for Callisto.

In terms of the information they’ll be collecting, Cochrane told us it’s not necessarily different data. Rather, it’s more data.

“Proving the existence of Callisto’s ocean from new measurements simply comes down to the fact that there are more measurements available to analyze,” Cochrane said. “For every flyby that occurs for each of these missions, only a very small snapshot in time of the magnetic field environment is captured by the magnetometer.”

Cochrane said the data from the Europe Clipper and JUICE missions will help “fill in the holes” from the Galileo mission, hopefully letting researchers finally prove whether an ocean exists on Callisto. The extra data will also help researchers estimate how thick Callisto’s ocean layer is, as well as the thickness of the ice shell that rests on top of it.

Could there be life on Callisto?

NASA and the European Space Agency wouldn’t have sent missions to Jupiter without good reasons to do so. And one is this: Europa’s hidden waters are the front-runner for extraterrestrial life.

“It is possible that Europa’s ocean can support life because we know that it hosts the key ingredients to support it, those being water, essential chemical elements, and energy (e.g. heat source from within) over a time span long enough for life to evolve,” Cochrane said. “Europa Clipper is actually a habitability mission (not to be confused with life detection) which will provide the data required to better help us answer this question. Until that time, it’s hard to comment on whether it is probable.”

But there’s a growing case for life on Callisto. It has a surprising amount of oxygen, and no one can figure out where most of it came from. Pair that with the increasing likelihood of a subsurface ocean, and though it’s still far from a sure thing, that’s enough evidence to justify taking a closer look at the Jupiter moon when the missions arrive in 2030 and 2031.

Read the full article here