Taylor Swift’s ordeal with a creepy stalker has inspired a New York state bill that would track mentally ill defendants in low-level cases and help them get treatment — in hopes that they’ll be less likely to be busted again.

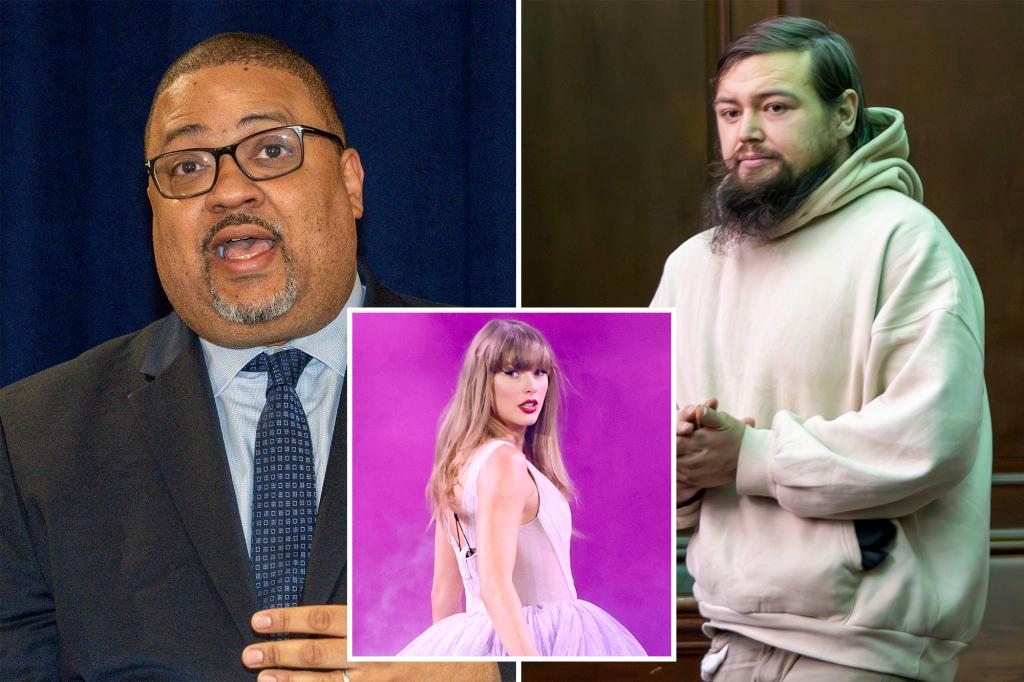

The proposal backed by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg and sponsored in Albany by Democrats from Manhattan and Queens aims to close a loophole that each year sends hundreds of misdemeanor offenders to fend for themselves when their cases are tossed after they are found “unfit” for trial.

As of now, such people — who are accused of crimes like third-degree assault, aggravated harassment and trespassing — automatically get their cases thrown out, and are released from the psychiatric hospitals they were held in within three days.

The new bill would assign case workers with the state’s Office of Mental Health Services to help get those defendants treatment after their release — including by regularly visiting them at home or in their community — and would require the hospital that releases them to make referrals for them.

The so-called “SUPPORT Act” aims to reduce recidivism, or the likelihood the person will be charged with another crime, and lower the risk of them being victimized by a crime themselves, the DA’s office said.

“Defying logic, our laws dictate that hundreds of people who are found unfit to stand trial by mental health professionals have their cases dismissed and are sent back to our communities without the necessary tools to access potentially life-saving treatment,” Bragg, a Democrat, said in a statement.

The new bill would “ensure these individuals are able to access robust services and are supported throughout, giving them a much better chance at lasting stability and decreasing the likelihood that they reoffend,” the DA added.

The legislation comes months after Bragg’s office charged David Crowe, a 33-year-old Seattle law student, with serial lurking outside of Swift’s Manhattan apartment. Crowe was released by a judge in January 2024 only to be found rummaging through a dumpster near her home an hour later.

The misdemeanor case was then dismissed the next month after Crowe was found mentally unfit to stand trial.

But unusually, instead of Crowe getting released from custody, he was turned over to an Upstate New York hospital for further treatment — due to the realization that he would likely have turned back up outside of the superstar’s home without additional intervention.

Crowe’s case highlighted that there could be another path for defendants who are set to be released but still need help, according to a spokesperson in the DA’s office.

In 2024, the misdemeanor cases for 224 defendants who were found unfit were dismissed, and in 2023 274 of such cases were tossed out, the DA’s office said.

Requests for so-called “730 exams” — court-ordered evaluations of whether a defendant is fit for trial — are on the rise as well, the office said.

As of June 2024, these exam requests were up 16.5% from the prior year, Bragg’s office said.

It was not immediately known if Crowe was still receiving treatment at the hospital.

The state Office of Mental Health declined to comment, citing patient confidentiality, and the Department of Correction said Crowe hasn’t been in its custody since he was released to the hospital in February 2024.

Crowe’s lawyer at the time, Katherine Bajuk with the New York City Defender Services, said her office no longer represents Crowe and that she wouldn’t be able to share confidential information about his medical care. But Bajuk said the NYCDS supports the new bill.

It was not immediately clear if Crowe had a new lawyer.

The bill only applies to accused offenders in misdemeanor cases because defendants in felony cases who are found unfit for trial are forced to stay in psychiatric facilities unless or until a doctor finds them to be fit again, under state law.

The bill’s backers in Albany are Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal (D-Manhattan) and Assemblyman Tony Simone (D-Queens.)

“There are simply too many individuals struggling with mental illness languishing on the streets and in the subways of New York City,” Hoylman-Sigal said in a statement. “If we are to seriously address this issue, we must focus on getting those with severe mental illnesses the help they need.”

Read the full article here